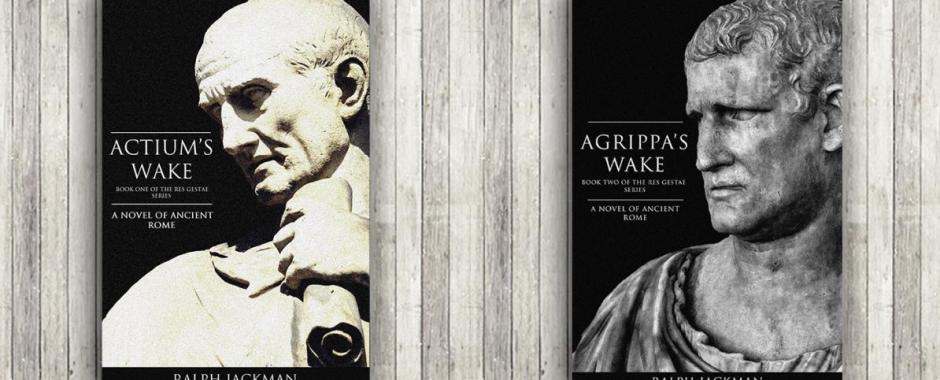

Read an extract from "Agrippa's Wake"

An epic tale which delves deeply into ancient traditions: 5 Stars

To Becca, Esme Rose, Baby Jackman, Mutti, Ellie and Henry,

For my father

Andrew Jackman (1946 – 2003)

Reading the inscription on my gravestone is a haunting experience. According to the skilful carving, I have been dead now for long past a decade. It is true that many times I have been close to death, and it is because of death that I sit down to write once more. But not mine.

Owls flit through the streets as I write, in numbers never before seen. Lightning strikes sacred places. The night sky is lit by a comet, a baleful portent; all around there is fear. And well there might be.

For Rome is in grave danger.

Before my ‘death’, I wrote about Octavian, Rome’s first king for hundreds of years, about my personal ruin at his hands, and about my beloved Republic’s fall. My proclaimed role at that time was to be the man who did not flinch from the truth. I step into that role once again.

Octavian is still the king of Rome, though he does not use that title. He has changed his name. Several years ago the senate in their sycophancy granted him the title of Augustus, marking him out as greater than mortal. I still call him Octavian.

Marcus Rutilius Crispus, meanwhile, well, he is dead; no status, no rank, no influence, and the Republic he loved is nothing but a memory.

But I, I am still very much alive. I have been on a journey worthy of an epic by Virgil, though, unlike Aeneas, I am no hero. I have done many deeds I am ashamed to have done, thought thoughts I reflect on with regret, but I have at last found peace. I will live my final years as a good man, worthy of the Rutilian name I lost, worthy of my father, and worthy of my family.

I suppose that my suicide is where this account should begin.

I

It was Octavian who ordered me to die. Most men have reasons to be ashamed, have deeds that do them no credit. Perhaps the greatest stain on my character was that I could not fall on my sword. A lack of courage? Maybe. A sense of injustice? Certainly.

I could not accept that Octavian, who had carried out more and bloodier deeds than the world had previously witnessed, would sit on a throne as sole ruler, while I, with justifiable faults driven by desperation, should be forced to die by my own hand.

Nevertheless, on that cold and windy evening, with Octavian’s agents closing in, I walked into the sea expecting to drown.

But the sea was cold. Very cold. Too cold. I could not do it. I could not go into the deeps. I could not force myself to die.

I looked behind me. I had to think of another plan. I knew I did not have much time. As I began to shiver uncontrollably, I had an idea.

I could escape. If I could slip away unseen, it might just work. Whether I carried on into the water to my death or ran away, one crucial fact would remain.

They would find a pair of sandals on the beach.

As quickly as I could, I waded back to the shore. I can still feel the pain in my body from the chill. I tore off my wet clothes to get them away from my skin, preferring to be naked, even with a night time breeze.

I do not know if I had already noticed a small fishing boat as I waded out to the water, or whether I spotted it at that moment, as I stood on the shore, a former senator stripped of everything.

I gathered the wet bundle of clothes into my arms, and ran through the shallows to avoid leaving a trail of footprints.

Octavian’s agents would only find that pair of sandals. I hoped that would to convince them.

I swam out to the boat and clambered aboard. It rocked as I hauled myself in, scraping my naked flesh on the side. Afraid that Octavian’s agents would arrive at any moment, I fumbled for the anchor and heaved it in as quickly as I could. Within moments, I was sat at the oars, frantically rowing to escape the shore.

It was not long before I had rowed as far as I could. My arms, legs and back were burning with the effort. I shipped oars and drifted, directionless, hopeless, in the lap of the gods. After a while, I decided to find out what else I had been fortunate enough to acquire in my new fishing boat.

I sliced my finger on an iron fishing hook. Despite the pain, I was delighted. With a fishing hook, as long as there was a line as well, I might eat. But there was no bait, no flies, no spiders, no worms.

It was as I pulled my tunic back over my head that I remember kicking what felt like a pile of stones with my unprotected toe. I confess, I swore. But this too was good news. The pebbles were attached to a net, a small drag net, though in the dark I could not see what condition it was in.

If the fates were kind to me, I would be able to fish. And if I could fish, I could survive. My father had taught me one crucial lesson about the sea. If ever I was stranded without water, I should drink fish blood.

‘It may taste foul,’ he said. ‘But it will keep you alive. Whatever you do, don’t drink the sea water. You’ll be dead in hours.’

So began one of the harshest, most painful episodes of my life. When it was over. I believed it had lasted only a couple of weeks. In fact, it had been nearly six months.

I had no intent of direction, other than to avoid land at all costs. So, I went out to sea until there was nothing in sight, whichever way I looked.

I was weary. I could not row any longer. And so I gave up, allowing the sea to take me wherever the gods intended. Day after day, the sun poured down on me mercilessly. The sea and sky merged into one deep blue. My skin burned, then developed rashes. As time passed, it dried out and began to crack. From time to time I would plunge into the sea to cool off but the water stung my wounds. I learned to make sure my tunic had dried before the evening. Because no matter how hot the day, the night was cold.

I managed to catch small fish with the lines, and in the first weeks, I can remember beating the surface of the sea with my oar to scare a shoal into my net.

But with time, I had no energy left to lift the oars.

The small fish I did not eat. Instead, I used them as bait to catch something bigger and better. I dreamt of catching a mullet, like the ones I had tasted so many times, and seen painted so life-like on so many walls.

But no mullet was forthcoming.

Aristotle believed music would lure fish or crabs, but I had no flute.

It seemed to me that fishing was going to be like so many other things in life I had set my hand to. Something I would fail at.

As the days passed, and by some miracle the gods preserved me, my eyes began to hurt, especially on sunny days. The reflection from the water dazzled me, until I felt that I would not even be able to see land if ever I did come across it again.

Just as I felt my skin would destroy me, and the pain of the boils and rashes on my hands, elbows and legs was growing too great, Neptune sent a rain storm. It nearly sank the boat, but it soothed and preserved me. Until I began to feel sick from the rocking of the boat. And that sickness lasted for days.

So it was that I stranded myself out at sea in that stolen little fishing boat. Delirium set in and I lost track of time, track of my mind, track of anything.

I can still feel the pain of my cracked lips and just how dry my mouth became. It was a torture of the most painful kind. Longlasting, enduring, with no end in sight.

Looking back, I see it as punishment for allowing my slave-girl Whisper to suffer torture on my behalf, just to submit false evidence in a trial in which I was selfishly trying to secure money for myself.

Whisper suffered greatly. Now, I know her pain. I know the shadow and scar of wounds which will never heal.

On one occasion, I vividly remember wanting to die as the sun had been baking me for so many hours, but a squall and a storm came, drenching me in rain. The cool drops of water were probably saving my life, but the anguish that I had no means of capturing any of the water to store for later was excruciating. Rainfall never fell frequently enough.

Bearded, burned and scarred, I collapsed in the boat, with my drag net floating hopelessly in the water, and my line of small fish dangling as feeble lures for bigger prey. It felt tragically ironic. I had achieved committing suicide after all.

But it was not my time to die. One day, land appeared on the horizon. I did not know where it was, or how far away it was. I just knew that if I did not get the boat to that shore, I was going to die.

For the first time in weeks, I lifted the oars back into position. It took nearly all of my strength to achieve even this. My legs had no power left in them, and my arms had wasted away till they looked as thin as a young boy’s.

With everything I had left, I hauled at the oars, guiding the boat slowly into land with the tide. Slowly, oh so slowly, the boat beached. I slumped out of it, feeling the relief of hot sand on my face.

I managed to drag myself towards the trees that were just off the shore, seeking shade from the sun. There I rested for a while.

I do not know how long I slept, but I was woken by the sound of music. At first, I thought it was a dream, but I could see the flicker of torchlight. It was a villa, and I heard the sound of plate and cup. Someone was dining.

I staggered to my feet and headed towards the music, propping myself up on tree trunks until, at last, I made my way step by step up the path to the door.

I knocked, and was greeted by a burly doorman, who seemed surprised and unimpressed by my presence.

I suppose I must have smelt terrible, unkempt and was wavering on my feet. He concluded that I was drunk and, without a word, shut the door in my face.

I tried again, desperate to speak and show by my language that I was not a vagrant. But the door was not answered.

I lifted my face to the heavens and called on the gods.

‘Help!’ I bellowed. ‘Help!’

Still the door did not open.

Distraught, defeated, but determined to try elsewhere, I tried to make my way back down the path to seek another house.

I did not make it. Half way down the path, the world spun one too many times and I collapsed.

The next months were a blur. Apparently I was rescued by the curiosity and kindness of the lady of the house, Aemelia. She had seen my faltering approach to the house through the window. When the doorman reported on me, the dinner guests debated on what should be done. In the end, Aemelia concluded that she lived in so remote a place, it was bizarre for a beggar to be lingering there. She did not even know that I had collapsed in her garden when she sent out slaves to recover me.

And so it is that I owe Aemelia my life. And I hope she knows how much I appreciate what she did that night.

Then came the questions. How long had I been sailing? Where had I come from? Who was I?

The first I could not answer. I guessed at a few weeks.

The second I kept simple. From Rome.

As for who I was, well, Marcus Rutilius Crispus was dead. So I took up the name Sextus, my late friend and comrade who fell on that fateful day in Actium, where my destruction began.

I distinctly remember a conversation about my boat.

When I suggested I had only been sailing for a few weeks, my answer caused consternation.

‘He can’t have been sailing for only a few weeks. Have you seen the barnacles on that boat? To have that many he must have been at sea for months...’

‘For months? But that’s impossible.’

‘Not impossible, clearly, but certainly improbable. He’s a lucky man, this Sextus.’

That was the first time I had been described as lucky for a long while. Perhaps I should have seen that as a new beginning. But that came later.

A few weeks passed and I was strong enough to stand. I had to deflect the endless questions, well meaning though they were. My story as a fisherman was too vague. I could see them doubt that I was truly a man of the sea. So as soon as I could, I took my leave of that household. With new clothes and fresh supplies to set me on my way, I would go wherever the gods took me. I did not care. I was just grateful to be alive.

And that is how I failed even to kill myself; the last in a succession of failures.

Or perhaps not. For when I disembarked from that boat, Marcus Rutilius Crispus was, indeed, believed to be dead. Within months, a gravestone declaiming his life’s achievements stood tall beside that of his wife, Olivia’s. All that remained of him was a nomad, travelling under the name of Sextus. The last mark of my old life was the scar on my left cheekbone from the battle of Actium.

Oh, the battle of Actium. Another of Agrippa’s great successes, but the scene of my demise. When I wrote that history, all those years ago, I did not have time to tell my tale of Actium, to explain how I made my mistake, the mistake that cost me everything. My sole purpose then was to reveal the nature of Octavian, Rome’s king.

Now, I wish to justify, or at least explain, that I was not always a bad man. I was a senator, a commander of a fleet, a good husband to Olivia. But the wake of Actium, swept this all away, and more. Even the Republic died that day.

Years have passed since I stood aboard the Triton at Actium. Nevertheless, I can recall the day’s events with absolute clarity.

‘Is she a witch then sir?’ My comrade and dear friend Sextus stood beside me.

‘Come now, Sextus,’ I replied, ‘surely you don’t believe that? You’re far too pragmatic to believe in such nonsense. She certainly is different though.’

‘Well, if she’s not a witch, then Antony’s no Roman,’ sneered Sextus. ‘I’ve heard he anointed her feet, in public. A true Roman wouldn’t do a thing like that.’

‘No indeed. But there’s something about Cleopatra. Even Caesar couldn’t resist her. I wonder what he’d think about Antony becoming her lover. Not quite the loyalty he expected I’m sure.’

We stood, side by side, as we had stood so many times, looking out towards the harbour. There, two towers had been strategically constructed on either side of the bay, guarding our prey. We had them trapped, and it looked as if, at last, after so many years, there would be a decisive outcome.

‘What are the latest reports, sir?’ asked Sextus. I can still picture the weariness in his face, his worn breastplate.

‘The news is good,’ I said. ‘The storm last night upset their fleet much more than ours and they say their troops are suffering with dysentery. The gods appear to be favouring Octavian.’

‘Rutilius old friend, you don’t seem to believe in any of this, in what we’re fighting for...’

I knew that a wavering mind in battle was useless, and it was not a good example to my men.

‘Sextus, I want peace as much as anyone. Peace and loyalty. If there were more loyalty in our world then maybe we would not be suffering such strife.’

‘But don’t you hate Antony?’ Sextus asked.

‘Hate is a strong word, Sextus. Of course I disapprove. Of what he’s doing, of what’s he done. But no one can deny that he’s under Cleopatra’s spell. Lust does strange things to a man. He was a great Roman. Things could have been very different.’

‘But sir, he ponces around the streets like a poxy king. He even dresses like an Egyptian.’

‘So they say,’ I replied.

‘And what about his will? You can’t ignore that, trying to give Cleopatr the eastern half of the Empire.’

‘No, of course not.’

And there was the power of politics. In Sextus’ mind, there was no doubt about the validity of the will which Octavian had read out in Rome. That document gave Octavian his pretext for war. Who would dare to suggest it might have been a forgery?

‘If I’m going to risk my life,’ Sextus said, ‘then it’s got to be worth it.’

If I had truly believed that Octavian was going to restore the Republic, then I would not have had my troublesome doubts.

‘It is worth it,’ I said. ‘And with Agrippa in command, we cannot lose. I must check on the men.’

I paced along the deck. Beneath me the rowers sat, layer upon layer, rank after rank. Lives as much as oars lay in their hands. The oarsmen chief had reported that all were fit and well, but the heat under the deck must have been stifling.

When I reached the stern, I nodded at the helmsman, who stood by the rudder. Even that grizzled campaigner looked apprehensive.

‘Have no fear. Victory will be ours,’ I said.

He stared out at the bay. When would it begin?

I marched along the deck inspecting the marines, their armour, their weaponry, their attitude. All acknowledged my presence. A few were gambling. Most stood or leaned against the side of the ship in silence. My confidence grew as I looked in the eyes of each man and knew that they believed in the cause. They were italian legionaries, the best kind. Their armour gleamed in the bright September sunshine.

I had never been involved in a battle on this scale. Our fleet stretched out as far as I could see, and beyond. All around I could hear the creaking wood as we sat, waiting.

I walked to the bow of the ship, fully one hundred and twenty feet from the stern. Soon, the entire deck would be teeming with war. At the front of the ship stood the ‘grip’, Agrippa’s brilliant invention, a variation of the catapult. Five years ago, the ‘grip’ was unleashed for the first time at Naulochus. Our enemy that day was Sextus Pompey, son of Pompey the Great. He had had no answer.

Now, once again, the heavy grapnel was locked in position, laden with the weight of our expectation. The four marines in charge were checking the ropes and lines attached to the winch.

‘All ready?’ I asked.

‘Yes sir. The ropes are clear and we’ve sharpened the grapnel.’

‘Good. It’s time to earn our reward. Aim well.’

They continued about their business. I looked up at the grapnel above my head. Its iron claws reached out, clasping for prey. I prayed that it would stick hard and true on the enemy’s deck.

As I made my way back towards Sextus, I checked that the standard catapults were prepared. Boulder upon boulder upon boulder was stacked around them. All was ready.

It was time for a brief speech. I stood in the centre of the deck and turned slowly so that everyone could hear me.

‘Comrades, the time is near when you will earn yourselves glory, riches and renown. Now is the time to earn your rewards. Now is the time to earn with your right hands the honours that you deserve. And by the gods we deserve it.’

I returned to Sextus’s side, taking my spear from him.

‘A bright dawn, sir,’ he said.’

‘Indeed. A shame it is wasted on this wretched war.’

‘Perhaps it’s a sign of a new beginning. Maybe the omens are good.’

I never answered. A horn sounded across the bay. Its call lingered for many seconds, a numinous tone. Immediately my soldiers were on their feet, apprehensive.

‘That is no horn of ours,’ I called, ‘Comrades, to your posts.’

The Centaur sailed passed, its figure head of a horse leaping over the waves.

‘Captain,’ Paullus, my newest recruit, called, ‘They are signalling. Put out. Engage the enemy if they do not withdraw.’

I called down to the Oarsmen chief, ‘Put out!’

There was a shout below the deck. With a rumble the great oars of our fleet began to strike the water in unison. Slowly we advanced, to the ominous rhythm of the rowers. Soon we were heading briskly towards the enemy. The din of the oars sent a surge of fear through me. I said a short prayer to Fides, my protectress.

As we closed on the enemy, I fought with my conscience. I had always struggled to come to terms with killing fellow Romans. But whether Egyptian or Roman, I had to be ruthless. They would not hesitate to exult in claiming the life of an officer and a senator. I steeled myself. Never would I be ruled from Alexandria.

We drew close enough to see that we had the greater numbers, but they had the larger ships. They loomed over us.

‘Rest your oars,’ I shouted.

‘Rest oars,’ came the muffled command through the deck.

The oars clattered and rattled. And then silence.

There was a pause.

I could feel the wind sweep across my breastplate, tugging gently at my spear. The water lapped against the side of the boat as we slowed to a complete halt.

There was still about a mile between the ships. I doubt there had ever been two such mighty fleets drawn up against one another. There we were, the two armies of the Empire, just outside the bay of Actium, until that day little known Actium, ready to determine the rule of the world.

The faces of my men showed no fear. They pressed against the side of the ship, straining to catch a glimpse of the enemy. Some checked their armour, and the grip of their shield, others drummed their fingers on the shaft of their spear. Killing fellow Romans had become second nature to them. I envied them.

We watched. We waited.

Behind the front line of marines stood our archers. As time passed, and there was still no action, some began to restring their bows.

‘Courage comrades,’ I called. ‘Victory will be ours. Spoils will be ours.’

The men let out a roar of feral ferocity. The Centaur, still sailing beside us, took up the call and soon our entire fleet was bellowing a war cry. I felt a prickle down my back. I was ready for action. I lusted for it.

I spotted a signal from our flagship, the Minerva. Two wings were to encircle Antony’s fleet. We formed a crescent of death around him, compelling him to engage.

‘For Rome!’ I shouted.

‘For Rome!’ the sea returned the call.

It was at that moment that I made my oath, the oath which I had to go to such great lengths to fulfil.

I turned to Sextus.

‘Witness this oath. If we claim victory today, I will build a temple for Fides.’

‘Fides is no goddess of mine, sir,’ Sextus replied.

If only she had been.

‘Why not?’ I asked. ‘You said that the sun may herald a new day. Maybe it heralds a new divinity for you too. You say you need a cause to fight for. If money’s not enough, then fight for Fides.’

He grinned at me. Gripping his spear he roared, ‘Roman Victor!’

Again the cry came back, ‘Roman Victor!’

And so it began.

As I predicted in my earlier history, the poets have sung of Actium. It has been immortalised in song as a great battle, worthy of its great contenders. In truth, it was much less than that. The catapults were fired. The sky was filled with stones which smashed into decks or plunged into water. Arrows pierced the air on their deadly flights and many men fell, but in the end it was Cleopatra’s courage that failed. She would flee, leaving the outcome of the battle certain.

We were the victors.

That is not to say that the battle was free of blood. It was the most gruesome I have witnessed. Since our ships were so small compared with the monstrous warships of Antony, we used cavalry-like tactics, charging and retreating like waves on a beach. By doing this, most evaded capture. Those that were grappled, though, were buried in rocks and arrows.

As for myself, my Triton sank many enemy ships, including the Neptune. It felt wrong to be attacking one of my own gods.

In the midst of the mayhem, a pathetic sight stopped me. In a soldier’s arms lay the body of a comrade, riddled with arrows.

He turned his raging eyes on me. ‘Roman arrows! These are Roman arrows!’

The full horror of the civil war had dawned on him. I could find no words of comfort. I pulled him to his feet and back into the fray.

As I write this, I am filled with remorse. The officer I describe in Marcus Rutilius Crispus, I admire. It is hard for me to accept some of the things I have since done. Especially when I consider that Agrippa faced many challenges, just as I did, but he never lost his nobility or principles.

My first error of judgement, a signal of the turning of the tide in my life, occurred not long afterwards. My face still bears the scar from the wound.

I commanded the helmsman to aim alongside the Osiris to snap its oars. High risk, as it was so close range, but, if we succeeded, the enemy would be stranded.

It looked as if we would make it. The rowers lost their grip as their oars shattered and splintered. I crouched behind my shield, feeling tired. Even then my age was beginning to show itself, and at a most inopportune moment.

The oarsmen were exhausted, but fear of death drove them.

Until the boulders landed.

The Triton’s deck splintered and collapsed, crushing all who were beneath it. We were floundering.

I raged that I would be slain by a coward at a distance and condemned to a tomb of water. I called on the men to board the Osiris. It was on the deck of that accursed ship, that I suffered my first ever wound in battle. Too late I saw an axe swing to my left. I spun round and slashed the attacker’s arm. My cheek was struck a savage blow. It was agony, but I could see that the attacker’s arm was nearly severed. As my vision turned red with blood, I stabbed forward with my sword and skewered him.

Young Paullus fell on the Osiris. The helmsman charged at him with a grappling hook. Paullus never saw the blow. The prongs pierced his helmet and he fell. I thought we were done for, that death would come, but by the gods’ grace, another of Octavian’s crews boarded the Osiris and saved us.

We joined their ship. My men were few, thirty at the most, but I was relieved to find Sextus was still alive.

‘You could tell they weren’t true Romans,’ he growled. ‘No fight in ‘em. That’s what comes of being slaves to a woman.’

The battle dragged on, losing momentum. Antony’s warships were floating fortresses, unbreakable. We were using pikes to hack at the turrets of an enemy ship when I heard Captain Duilius call out.

‘Rutilius. The first of Cleopatra’s ships have hoisted sail. They are fleeing! Look! Not one is engaging.’

I felt a rush. More relief than joy.

‘Curse this wind,’ I said. ‘It’s strong enough for them to escape.’

Duilius saw my cheek was still pouring blood. He summoned physicians. I waved them away.

‘Not until the end.’

News of Cleopatra’s flight spread. What would happen next? The great purple sail of Cleopatra’s ship, the Antonias itself, was unfurled.

‘Roman Victor! Roman Victor!’ The cry went up.

Our enemy was thrown into confusion, even Antony himself. They were given the signal to retreat. All about us, sails were raised.

To gain speed, the turrets which we had just been working so hard to break were thrown overboard by the very soldiers who had been defending them so fiercely. It was total chaos.

‘Duilius,’ I called, ‘Why are we letting Cleopatra escape? Let’s kill her.’

Duilius shook his head. ‘We have no sails, and the oarsmen are exhausted.’

I was about to protest when he held up his hand.

‘Octavian’s orders were to stop fighting at the earliest possible opportunity. The fighting is over.’

‘But the money Captain,’ I argued. ‘It’s on the Antonias. Think of the reward if we were the men to capture her. You say the fighting is over. Look around. The fighting is far from over. We outnumber them. Let’s crush their attempts on the Empire once and for all.’

Duilius held firm. ‘Octavian’s orders were clear.’

I watched as the faster of our ships set off to pursue Cleopatra.

‘But this is our chance for glory,’ I cried. ‘This is our chance to earn reward for what we have lived through.’

But Duilius would not change his mind. Instead, we joined a blockade to the north, where the fighting, not at all close to finishing, continued until dusk.

I often wonder if I could have done more to persuade Duilius to change his mind. Had we set off in pursuit, even unsuccessfully, it would have changed my fate. I would not have made my ultimately fatal mistake.

As the daylight failed, orange light caught my eye. I pointed across to the Minerva. Behind it, more warships were arriving from our base on the shore, laden with fire. We fell back to be issued with many arrows. A blaze was lit the deck, while hundreds of javelins with flaming torches attached to them were brought on board.

Now the battle changed in appearance. Flames covered the sea. The air was filled with jars of pitch and charcoal, fireballs of death. The fire ate through Antony’s fleet. Soldiers desperately threw their drinking water to douse the flames, but the fire kept spreading. Men burnt like torches. They tried to use their cloaks to smother the flames, then the bodies of the dead. Smoke rose up and a dreadful smell lingered. The breeze stiffened, fatally. It cooled my face, but fanned the flames as the fire licked with tongues of death.

We withdrew to a safe distance from the burning ships and watched our enemy die. Some fell, choking in the smoke, others were incinerated in their armour as it glowed red with heat. I walked to the archers on the ship.

‘Pick them off. They are unprotected.’

With unerring accuracy, they were felled. As they realised all hope was lost, those with any wits remaining jumped overboard. It was a great fall. Too great. Many made no stroke when they landed, but drifted on the surface of the water, lifeless.

I crossed to the port side. There, on the deck of another floundering enemy vessel, in the midst of the flames, I saw soldiers killing each other, putting an end to their misery. The sight filled me with a sudden dread. How could I possibly feel pleased by what I was seeing? These men were Roman citizens. They had probably even fought for the glory of Rome in the past.

‘Hold back,’ Duilius called, ‘Victory is assured.’

A mighty cheer went up.

‘Let’s get the plunder!’

Duilius shook his head. ‘Our instructions are to stay away from the blaze.’

There was a clamour of dissent.

‘We fight for plunder. You can’t deny us,’ growled a soldier.

‘There’ll be treasure on those ships. It’s ours,’ bawled another. ‘We’ve earned it with our own blood.’

Duilius looked unnerved. I can picture his face as vividly as if it was in front of my failing eyes now. And the reason I can see it so well, is because this was the moment I made my mistake.

I wanted the reward as much as the angry soldiers, for having to fight the sickening war.

I uttered the words which sealed the fate of Senator Marcus Rutilius Crispus. Little did I know it at the time.

‘They’re right. Let’s sail in, put out the flames and take all the plunder we want.’

As I was taller than Duilius, I stood over him, trying to intimidate him. I suspect my wound had some effect. He struggled to look me in the eye.

‘You were at the meeting,’ he said, his voice wavering. ‘You know the instructions. Any wealth belongs to Octavian. He is the commander.’

‘Are you denying these men reward for their loyal service?’ I challenged.

The soldiers pressed around in a group. Duilius gave in.

If only he had not.